All Shesheshen wants is to hibernate in peace, play with her wild blue-furred bear, and occasionally feed on an unsuspecting human. But no, the Wulfyre family will not leave her alone. After an attack, goo-based Shesheshen shapeshifts into human form and is rescued by Homily. She is an odd woman who, in spite of everything, finds Shesheshen amusing. The monster who isn’t very good at being monstrous and the maiden who is neither pure nor innocent make a surprisingly good match. So much so that Shesheshen comes to the realization that not only is Homily the perfect person to lay her eggs in but that she’ll die as a result.

Soon, the two women are dragged into the Wulfyre hunt for the wyrm (aka Shesheshen in her monster form), and all kinds of terrible things emerge from the shadows. If they want a chance at happiness together, a lot of bad people are going to have to die first. But those bad people also want them dead. Whatever happens next, it’s going to push Homily and Shesheshen to the brink.

This is one of those novels that is probably going to be a challenge to sell. I’m already seeing people calling it “cozy horror” and “romantasy”. While there are some horrific elements—lots of gore and body horror, albeit expressed in practical rather than horrifying ways—and there is a romance subplot, evoking those genres can lead readers to expect certain tropes and vibes. I’d put this squarely into general fantasy rather than one of the popular new marketing terms. It’s weird and unsettling, and it plays with elements of horror and romance without fully committing to those genres.

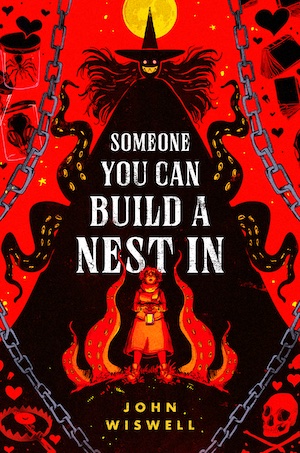

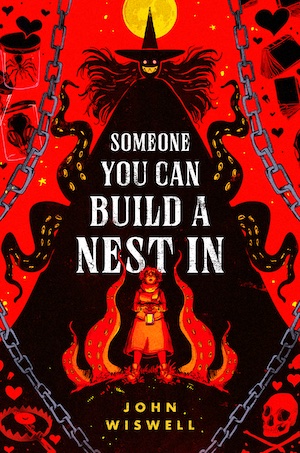

Buy the Book

Someone You Can Build a Nest In

I think it’s also important for readers to come prepared for queer shit. Not just queer as in LGBTQIAP+, but queer as in rejecting the norm, the traditional, and the socially acceptable. Queer as in revolutionary. Queer as in “fuck you and the assumptions you rode in on.” Shesheshen and Homily’s relationship is queer, as is the way Shesheshen interacts with the world. Remember: Shesheshen is a monster both literally and metaphorically. Her very existence violates social norms. She can “pass” as “normal”, or mask, if you will, but only by mimicking other people and practicing their behaviors. I’m neurodivergent and so much of Shesheshen’s experiences felt eerily familiar. The pragmatism, the frustration at not being able to figure out what someone actually wants versus what they say they want, the feeling like you’re pretending at being a certain kind of person when you’re really something else entirely. At times, she is overwhelmed by sensations that humans don’t seem to notice, and she reacts to things in a way that some humans would find cold and emotionless but is for her just the logical response to an illogical situation.

Something else that makes you feel monstrous? Being on the asexual and aromantic spectrums. Before I knew those words, I thought I was a broken person. I couldn’t understand attraction, so I had what I called practice boyfriends; maybe sex and love were like practicing the piano, and if I just dated enough someday it would all make sense. I felt unloved, unloveable, and unloving. I felt like I was playing at being a person. I felt alien and wrong. It took three decades for me to find asexuality and aromanticism, but it only took a few moments (and reading Julie Sondra Decker’s The Invisible Orientation) to realize I wasn’t broken, just shaped differently. Like Shesheshen, I also went through a metamorphosis where I could finally see myself for who I truly was. It wasn’t me who was wrong but the expectations the world put on me. I could live my life in a way that was satisfying and enjoyable to me. Let the allos be confused and uncomprehending for once. I know who I am.

Trauma and abuse can also make you feel like a monster wearing a person suit. Homily had a lifetime of torment at the hands of her family. She grew up feeling insignificant and unvalued. She felt unworthy of things other people took for granted. She was a thing to be used and pushed around, not a person who deserved support and protection. Coming out the other side of abuse means dealing with the resulting trauma. You basically have to shape yourself into a living person while cutting out all the things that are holding you back. But you can never quite get free of all those horrors.

So while yes, Someone You Can Build a Nest In is romantic, it’s an aromantic version of romance rather than an alloromantic one. I might even call it queerplatonic. Whatever it is, it’s hella queer. And that romance is also colored by Shesheshen’s neurodivergence as well as Homily’s trauma. Don’t come into this novel expecting allo-tinged tropes. And if this is your first exploration into the wild lands of asexuality and aromanticism, welcome. We do things differently around here.

The only real miss for me was the predictability of the plot. The plot was not nearly as inventive as the premise was. Part of that was the epilogue. It felt a bit like cheating, like Wiswell got to have his titular nest without all the accompanying violence. Maybe that was the point, or maybe the point was to do what Romance novels often do and flash forward to see how that HEA/HFN is going. I don’t know, but I’m not convinced it was necessary.

With his typical quirky humor and creative wit, John Wiswell’s debut novel Someone You Can Build a Nest In is a winner. I’ve been looking forward to his move from short to long fiction for a while now, and he did not disappoint. Aces and aros, this one is for you.

Someone You Can Build a Nest In is published by DAW.

Read an excerpt.